This past Thursday, a line of eighth graders snaked around the lobby, maskless and less than a few feet apart. Just a year ago, eighth graders looking to attend Bard Queens sat at home recording videos in place of in-person interviews.

This fall marks the first admissions period to require in-person testing and interviews since 2021. The current four grades at BHSECQ are the only four admitted through the Covid-19 adapted admissions process.

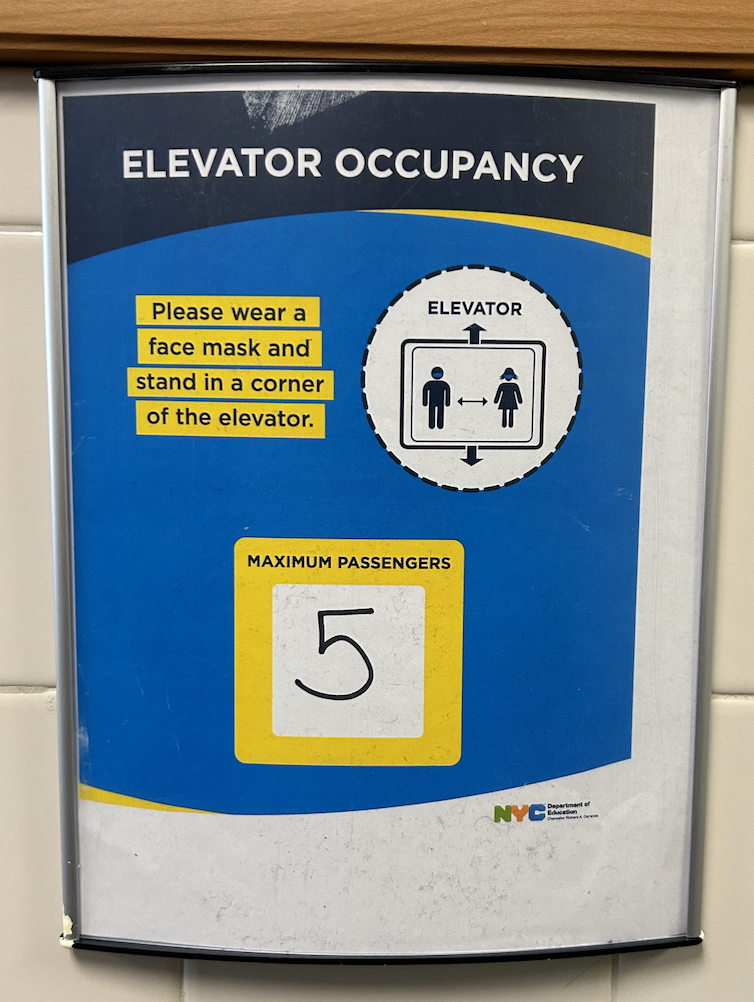

Walking through the halls of Bard, one gets a pretty good picture of pre-pandemic life, save the occasional mask or obsolete social distancing sign. Covid no longer seems an immediate threat to the school community. Its remnants, however, cast a shadow into our current academic lives: zoom links embedded in Google Classrooms “just in case,” a (much ignored) passenger warning in 6th floor elevator bay.

It’s been four years since students returned to full-time in-person learning, and teachers at Bard are still learning how much of their pandemic-style teaching to implement. Zach Pickard, a BHSEC Literature professor, talked about how Zoom acted as a window into his students’ lives in 2020. “It forced me to confront the fact that my students are dealing with more different things than I had realized.” Having been back teaching in-person for the past four years, in a classroom far removed from students’ home lives, there is some disagreement among BHSECQ faculty whether to return class rigor to its pre-pandemic levels. Some believe that keeping the pandemic era safety nets perpetuates sloppiness, that cutting students the slack that they did in the pandemic will prevent the school from returning to its intended prestige. Pickard, however, sees value in the patience learned through online education, offering full-credit extensions, and shortened versions of homework readings as an acknowledgement that “sometimes things come up, and there needs to be some space for that.”

One good thing that came of the pandemic was that students felt more comfortable to speak openly when struggling. Because of the collective feelings of stress and isolation, mental health felt easier to discuss in a school setting. “I found myself having a lot of conversations with students where I had to assure them that mental health was health, that in the same way if you broke your leg, I wouldn’t expect you to turn in a paper the next day. If you had a depressive crisis and wept all night, I’m not going to expect you to turn in a paper the next day as well,” Pickard said. One hesitation of re-implementing strict rigor is that mental health will move to the back burner in students’ academic lives.

Covid has exacerbated the feelings we’ve all been struggling with for the past decade – a rise of reliance on technology and short form content, and a movement away from using books as entertainment. “When I started teaching 20 years ago, you could already start to smell the decay – the sense that books were on their way to being over,” Pickard said. In online learning, “We were forced to be on a screen all day long, and you would think we’d be like ‘Oh thank God,’ schools over, I can get off the screen.” Instead, we fell into unhealthy habits, reaching again for our phones and computers after a six-hour school day spent on them. The reliance on technology became more critical than ever before, and intensified students’ likeliness to pick up a screen over a book in a moment of boredom. Because of the pandemic or technology, or more likely, some combination of both, “[students] just don’t know how to read anything that was written more than 50 years ago.”

Can teachers force this inability out of students? The Bard Queens administration is attempting to return the Bard student population to its pre-pandemic standards, using “an in-person reading and writing component, a math component, and an interview for admission to the school,” Principal Laura Hymson confirmed. Taking the application process from students’ homes and back into a school setting in the hope that they will function without the use of Artificial Intelligence or a parent standing over their shoulder. Using a pen and paper will hopefully serve as a true judgment of eighth graders’ abilities. This move away from Covid-precautious admissions could mean, finally, an incoming class that understands the true expectations of their work. It is difficult to say, however, whether a return to pre-covid admissions will mean a return to a pre-covid work ethic, but only time will tell.

Pickard did, however, share that his Y2 Sophomore Seminar class were “the first generation to turn in all of their essays on time since the pandemic,” adding, “forgive me for saying this, but I wouldn’t have picked them for that, because you guys were a bit of a mess in the ninth grade.” Four years after online learning, current seniors seem to finally be getting their act together. It may have taken their entire high school career, but the graduating class seems finally to be functioning in a somewhat pre-pandemic way.

Maybe teachers can force this return with rigor, or maybe all curriculums just need to adapt to a student body that doesn’t process difficult text like it used to. It seems an impossible question as an educator whether or not to loosen the strictness of post-Covid education. An incorporation of changes allows for a possible pandemic-era feeling of mental health openness and real-life acknowledgement. This approach, however, could mean furthering the loss of capacity to turn in assignments done with quality on time. As Pickard puts it, post-pandemic class policies need to reach “a sensible compromise with reality.”